Patients who suffer from cystic fibrosis have

been living longer and longer due to ever improving treatment options for the

disease, as explained in the post about cystic fibrosis. However, despite the best efforts of

researchers and physicians, patients will still frequently need a lung

transplant at some point in their life’s, because of the extensive damage

caused by the disease. This

procedure was not available for cystic fibrosis patients until about thirty

years ago1: this was evidently because of the increased risk of

infection in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis. As explained by Jens,

patients suffering from CF have an impaired innate immune system and a reduced

clearance of bacteria due to an altered innate immune response in the lung. While lung transplants prolong life expectancy of many patients, it still has its limitations. Transplanted lungs

generally don’t last very long, especially when a patient

suffers from frequent infections. The main complication in CF transplant

patients to date is infection with multi drug resistant bacteria, such as the

frequently occurring Burkholderia cepacian.1 Because CF causes damage to several organs

in the body, patients often have an extensive set of problems beyond the problems

in the lungs, which makes organ transplantation even harder and the patient

more vulnerable. The good news is that due to now quite extensive knowledge on

extrapulmonary complications in CF-patients, it is possible now to

transplant lungs to even severe cystic fibrosis patients even when they suffer from extensive

complications in other organs. Even though the procedure is now done quite

frequently in cystic fibrosis patients and has rapidly improved, it still

harbours a lot of risks. An example is the impaired immune function, which can have

great effect on the transplant success.4 Comorbodity has a great effect on transplant success too. Patients receiving transplants are often in a

later and more severe stage of the disease, which makes receiving successful transplants

and improved graft survival even more important.

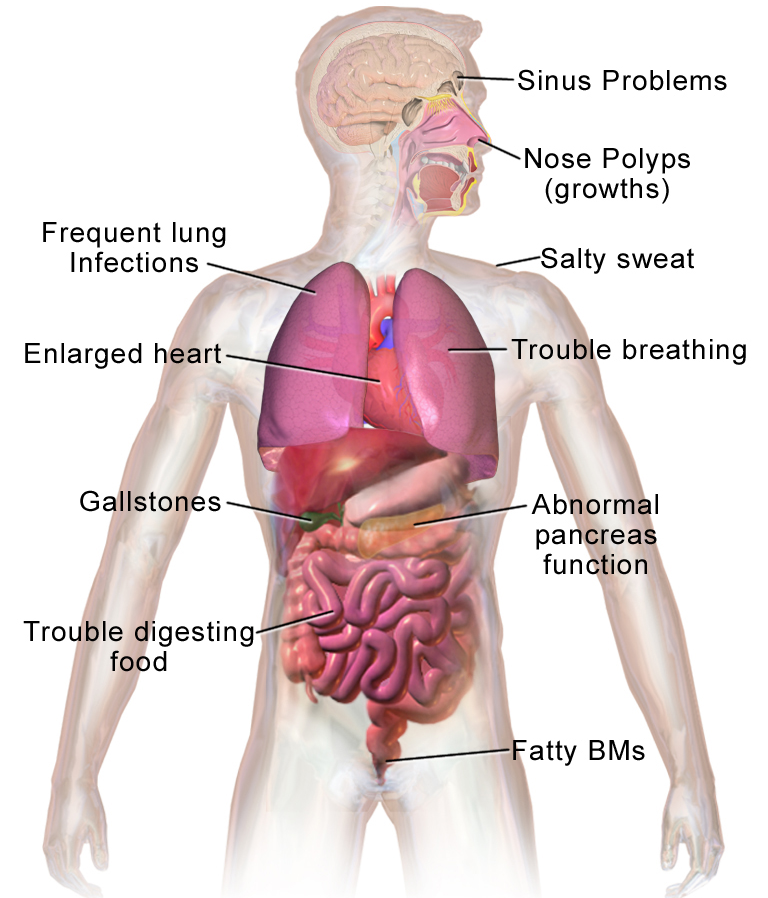

Figure 1 Possible additional

problems in Cystic fibrosis patients10

Are you curious as to how a lung transplant is

done? Below, there is video in which the entire procedure is explained:

Lung microbiome in survival rejection of

transplant

The lung microbiome is known to correlate with

survival in lung transplant recipients. In a study by Bernasconi et. al6,

they compared 112 patients post-transplant on long term graft survival

and the microbiome found in their lungs. The study showed that dysbiosis led to

more inflammation and unwanted graft remodelling which eventually led to a

worse prognosis. Furthermore, in a systemic review by Shasples et al.4 ,it is explained that infection and bronchiolitis obliterans are both key

players in long term graft survival. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) is

known to be one of the most important limiting factor of long term survival in

lung transplant recipients. BOS is stimulated by graft rejection and in turn

graft rejection is induced by dysbiosis and inflammation. For example, the bacteria pseudomonas fluorescens was oftenly found in patients who did not

suffer from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, while Pseudomonas Aeruginosa seems to have an association with the

presence of bronchiolitis obliterans2. While we now start to

grasp how a a healthy microbiome is defined and what microorganisms are

generally found, we can start associate certain microorganisms and the degree of

diversity to better outcomes or rejection prognoses, and adapt maintenance

protocols in these patients accordingly. Since the lung has the highest rate of

acute and chronic rejection of any transplanted organ3 , it is

important to understand how the microbiota are influencing this and whether we could

influence the lung microbiota to reduce rejection and infection.

Infections and transplantation

A donor lung has been ridded of its defence

mechanisms, including the important cough reflex. Not only are the lungs in

constant contact with the outside world, they also are exposed to the colonized

native airway. Furthermore, in the donor lung there is no bronchial circulation

and lymphatic drainage.8 In addition to this already vulnerable state, the

patient will also be on immune suppressants to reduce the risk of graft

rejection. The failure and absence of the usual defence mechanisms lead to a heightened

rate of infection.8 Which, as mentioned before, impacts the graft

survival. The use of antibiotics used by the patient when they do acquire an

infection will also increase the chance of reinfection and reduce the diversity

of the lung microbiome which, as mentioned before, adds to the vulnerability, as was

also discussed in the post by Malak. Patients are the most at risk of infection within the first year after transplantation; more than 75% of infectious episodes occur within the first year.9 The

more infections a patient has, the higher the chance of graft rejection and

damage to the lungs. Thus, it is important to keep infections to a minimum!

Infections and lung microbiome in transplanted CF

patients

If you would compare cystic fibrosis patients post-transplant

with patients receiving a lung transplant for other reasons, the diversity of

bacteria in CF transplant patients seems to be less, which as I previously

pointed out, is correlated with a worse outcome and an increase of infections.7

While one could argue that the CF patients who experience these problems are now

in possession of a healthy pair of lungs, this does not completely solve the

problem. So why do CF patients still differ in lung microbiome from that of

other lung transplant recipients? While I could not exactly tell you why, we’ve

seen in the post by Malak about the lung- gut axis that there is more

influencing the lung microbiome than the lungs alone and CF patients also have

problems in other organs such as the intestines. Moreover these CF patients

still suffer from a somewhat impaired and sometimes even overactive immune

system. So we can conclude, that

for this group of patients a different approach is needed when it comes to a

healthy microbiome and acquiring infections. However, there is more known about the lung microbiome in cystic

fibrosis patients than that of the general population3, which begs

the question if we could use this information to influence the outcome of their

lung transplants. In other words, our work has been laid out for us if

it comes to lung transplants in patients with cystic fibrosis!

Written by Elise van Putten

Written by Elise van Putten

References:

1. Cecilia Chaparro & Shaf Keshavjee (2016)

Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis: an update, Expert Review of

Respiratory Medicine, 10:12, 1269-1280, DOI:10.1080/17476348.2016.1261016

2. Robert P.

Dickson and John R. Erb-Downward (2014) Changes in the Lung Microbiome

following Lung Transplantation Include the Emergence of Two Distinct

Pseudomonas Species with Distinct Clinical Associations, PloS One, 9(5): e97214

3. Sushma K.CribbsJames and M.Beck (2017) Microbiome in the pathogenesis of cystic

fibrosis and lung transplant-related disease, Elsevier, Volume 179, January

2017, Pages 84-96

4. S.M. Palmer, L.H. Burch, A.J. Trindade, et

al. Innate immunity influences long-term outcomes after human lung transplant, Am

J Respir Crit Care Med, 171 (2005), pp. 780-785

5. L.D. Sharples, K. McNeil, S. Stewart, J.

Wallwork, Risk factors for bronchiolitis obliterans: a systematic review of

recent publications, J Heart Lung Transplant, 21 (2002), pp. 271-281

6. Eric Bernasconi, Céline Pattaroni and Angela Koutsokera, Airway Microbiota

Determines Innate Cell Inflammatory or Tissue Remodeling Profiles in Lung

Transplantation, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine,

Vol. 194, No. 10, Nov 15, 2016

7. E.S. Charlson, J.M. Diamond, K. Bittinger,

et al., Lung-enriched organisms and aberrant bacterial and fungal respiratory microbiota

after lung transplant, Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 186 (2012), pp. 536-545

8. BURGUETE, S. R., MASELLI, D. J., FERNANDEZ,

J. F. and LEVINE, S. M. (2013), Lung transplant infection. Respirology, 18:

22–38. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02196.x

9. Speich R, van der Bij W.

Epidemiology and management of infections after lung transplantation. Clin.

Infect. Dis. 2001; 33(Suppl. 1): S58–65.

10. Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical

gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2).

DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.